What is a historic landmark without a history? And what is a history without the voices of those who were affected directly by an event or institution?

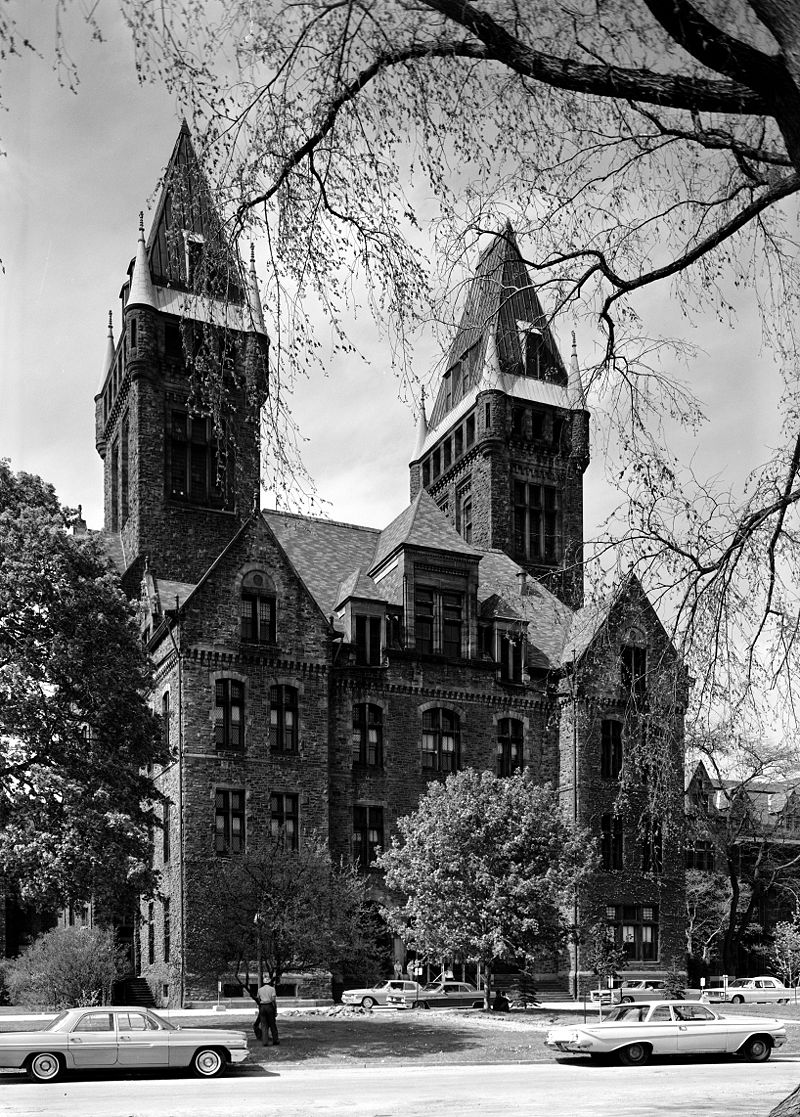

The revitalization of Buffalo, NY is exciting and promising for Western New Yorkers, and while it does not benefit everyone equally across socioeconomic divides, efforts to improve and drum up support for any part of the city should be encouraged and lauded. Sometimes, however, restorations and renovations raise ethical questions that should not be ignored.

The recent renovation of the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane into Hotel Henry seems impressive, noble, and empowering on the surface. The issue is that there are questions that have neither been asked nor answered to an adequate extent before the Buffalo Bandwagon and all its cheerleaders gave HH its blessing.

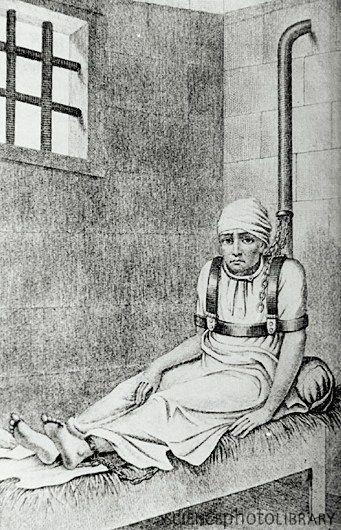

19th and 20th Century insane asylums are widely recognized now as horrifying places wherein patient-victims were not seen as human and, therefore, were treated inhumanely– chained to beds, kept locked in deplorable conditions, sometimes beaten, and often tortured with various “medical” devices and practices which were considered acceptable forms of treatment for socially aberrant behaviors at the time. Unfortunately, some of these practices have carried on into the 21st Century, haunting in a very real way some of the institutions we call hospitals today. The Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane was no exception to this rule nor to this history of despicable degradation, which is precisely why its transformation into a “grand hotel” should have been and continue to be interrogated and treated delicately.

Not enough has been done thus far to recognize the patients of that institution as victims. This is partly due to the fact that we, as a community and larger society, continue to think it is acceptable to treat people with cognitive differences as if they are subhuman and invisible. The references all over social media to Hotel Henry as “haunted” and “spooky” are indicative of this phenomenon: that victims of the mental health industry do not exist, or -if they do- only exist as folkloric, spectral entities not entitled to actual histories or to actual restorative justice.

The thought of a person who lost their liberty and then died, isolated and alone, in a bed at the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane, or at any asylum for that matter, now remaining unnamed in the psyche of Buffalonians haunts me. I am also haunted by the thought of Western New Yorkers getting tingles up and down their spines as they recline in a luxury bed, sipping a glass of wine, fantasizing about the horrors that “might have” taken place in their room. It goes beyond insensitivity and ignorance.

Here’s the issue. The treatment of those labeled mentally ill is not something to fantasize about or romanticize. It’s not something to trivialize. It’s something that should make you sick to your stomach, if you possess a conscience. It’s something that should make you solemn and mournful, in the way that you would be expected to feel if you were at a Holocaust memorial site. Human beings were rendered social outcasts and they were thrown away, cast off, mistreated, and defeated in the space that is now serving as a beautiful hotel. Revenue for our incredible city is being derived from the hotel, as it was from the asylum, but is this revenue helping people who have been affected negatively by mental illness stigma? My hope is that we start asking questions, as a city and a culture, about our own attitudes toward the institutions we are building and supporting. Hotel Henry may very well be a place that fosters respect for those who were victimized within and around its walls, but it cannot do so without acknowledging in a public way the lives, the victimization, and the very real although mostly erased history of those very people. The history of a group of victimized people is not to be glossed over. Questions need to be raised and addressed.

Here’s a question that I hope can be answered: have any significant and serious attempts been made on the part of Hotel Henry’s owners/management to honor, recognize, and pay respects to those who were imprisoned in and victimized by what was formerly known as Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane?

Restoration is one thing, but the erasure of an entire history of pain and dehumanizing treatment in the name of luxury and glamor is another. People are making fun and entertainment out of what was degradation and real pain and suffering for those who were committed at this institution up until the late 1970s. What if people were calling a former concentration camp “spooky” or “gorgeous,” with a tone that indicates titillation? What if they were holding their weddings there? Though of different origins and proportions, the use of asylums to silence and remove human beings from society is still a grave matter, and should be handled with the utmost sensitivity.

I hope at some point that a reputable local or national news source will address in greater depth the ethics of and complicated issues related to turning a site of incarceration, torment, suffering, and death into a “grand hotel.”

At the heart of this is that the majority of people do not understand what it means to be committed and force-treated. They do not understand what it is like within mental institutions. And if they do understand on the surface, if they have not been in an asylum themselves and treated as such, they do not and cannot know what it is like to lose their liberty, their reputation, their bodily freedom, their autonomy, their credibility, and their very lives. The stigma of mental illness renders people labeled “mentally ill” as virtually without a voice, unimportant, worthy of mistreatment, without an existence, erased.

There is no true restoration and renovation that is accompanied by erasure.

With restoration, comes responsibility: social responsibility. The best way for an institution like Hotel Henry to foster an ethically sound architectural restoration is to restore justice while doing so: giving a voice to those who lost their voices within its walls– those whose silent cries will forever haunt the hotel and its visitors if their history is not honored appropriately.

Some histories have been erased, and, sadly, for those locked in mental institutions, often the most disempowered among us, this is often the case. But this is something that needs to change. Hotel Henry can help by addressing issues of social injustice and by addressing the treatment of the mentally ill.

Articles like the above displayed (by Susan Glaser) participate in corporatizational myth-making by producing chic-sounding flippant over-simplifications that drum up excitement and expenditure for the hotel but that do so at expense of those who have been and are affected by the mental health industry and the stigma of mental illness. We need to be reminded that beautiful buildings do not equal beautiful behaviors in their interiors nor beautiful histories. Guests at Hotel Henry should come in attuned to the fact that they check in with their privilege: they are, unlike their predecessors, hotel guests– not prisoners.

The remote location of the former asylum reflects the social position of those labeled mentally ill in our society: they are put on the outskirts and moved away from “normally” functioning people. This further perpetuates the damaging stigma of mental illness. Architectural significance and the intentions of the architects who originally built what is now Hotel Henry are fascinating, but not as important as the untold stories of those who inhabited the asylum, those who inhabited other asylums, and those who currently are held in state mental hospitals.

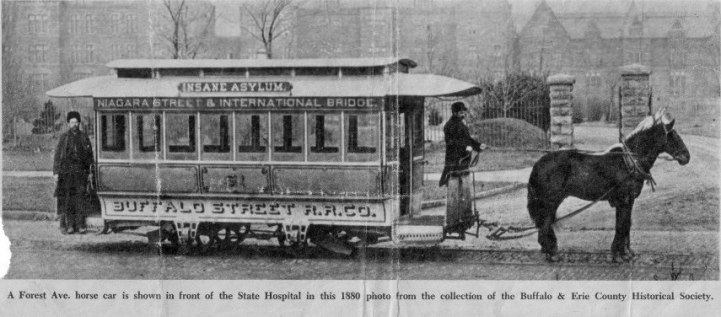

While there are images of what became the Buffalo Psychiatric Center that might seem on the surface to indicate that in the late 20th Century the BPC utilized “humane programming” (for white people only, apparently) –including an insane asylum… trolley–, the images offer only the tiniest and most carefully-curated fragment of the history of that building. The larger history of 19th and 20th (and 21st) century asylums tells a different story, a beyond-troubling one: one that, unfortunately, is too often dismissed, ignored, and doomed to remain a phantom of the American psyche.

I will end this attempt to raise the awareness of Western New Yorkers with a call to action for the hotel itself.

Hotel Henry: Please consider donating a portion of your profits from this project/enterprise, yearly, to humane and non-custodial mental health organizations and initiatives, and please be public about it and clear about your purpose in doing so. Please also consider putting out a very clear statement that addresses your position on the treatment of those labeled mentally ill.

The real restoration needs to happen in the way in which we view cognitive differences.

Jessica Lowell Mason

July 14, 2017

[Notes: The collage of photographs of victims harmed by early mental industry practices does not consist of photos taken at the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane. Very few photos taken within the Buffalo State institution are available to the public, and these should not be trusted as accurate indications of the BS Asylum’s practices because they were carefully taken, not by patients or family members of patients or members of the public but, by the institution itself for the purpose of constructing a one-dimensional, limited, and positive-but-inaccurate narrative about the practices within the institution, which had a monetary and reputational reason for doing so. The Richardson Complex buildings were designed in 1870. Patient records exist from 1881 to 1975, but, again, these records cannot be trusted to tell all, or perhaps any, of the comprehensive stories of the patients incarcerated in the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane because they were told from an oppressive perspective and constructed by people in positions of power who were operating under archaic and condemnable belief systems about cognition and mental health. Those who participate in the institutional oppression of powerless and marginalized groups of people cannot and should not be granted the right to speak on behalf of said people. Narratives constructed as the byproducts of powerful institutions that promote misinformation, enslavement, and degradation should be met with distrust rather than accepted blindly as the presiding narrative. A patient record in a 19th/20th century asylum should be considered carefully within its context: as a narrative constructed by an oppressive institution– not as a narrative that speaks directly to the experiences of the victims of that institution. Narratives from the mouths or hands of victims themselves, and/or their allies, should be figured into and placed at the forefront of our public consciousness and our historical projects. As long as the physician-patient relationship in the mental health industry is one built on an extreme disparity in power, medical narratives will continue to be visible, recognized entities of oppression while patient (humanistic) narratives will continue to be invisible entities that live mostly in silence with the oppressed. The mental health industry and our culture at large has to begin to recognize mental health patients as a disempowered community with a long history of victimization as well as its culpability in promoting corporate oppression and closing its eyes to the dehumanizing traditions practiced under its watch.]

I know for a fact that a book is being written about many of the patients who were in the Richardson Complex. My Dad was interviewed about his aunt who was there in the early 1930’s …

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is good news; thank you so much for sharing it! Best wishes to you and the book project. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this. I love this building and would love to explore how it has been adapted. I could never step foot in there though. My mother spent time there after I was born and the few stories she shared with me are horrifying.

I am highly empathic to human energy and I saw photos from a public tour done a few years ago, before any renovations, and sat at my computer and cried. I thought of my mother looking through those barred windows and others wanting to be free…of suffering.

It is hard to hear people discuss it but I am glad there is now joy to be found there. I am Buddhist and there is a teaching on turning poison into medicine.

Thank you for writing this piece. I do hope people have respect for this space above and beyond it’s gothic beauty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I cannot thank you enough for sharing this. It is an honor to have you do so. I am so sorry that your mother went through that. Her stories, I am sure, are powerful, and you hold those stories inside you, too. Thank you, also, for your support. Wow.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this sensitive article. It is something everyone should consider when checking into this hotel. I attended Buffalo State in the early 1070s when this was still a Psychiatric Center, and remember wondering what was going on in those buildings. Everyone who checks in should be aware of it’s history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been uneasy with this project since it’s inception, and I’m glad someone has spelled out those feelings that have been in the pit of my stomach.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hotel management wishes very much to erase the negative history of the building. They are trying to create a high-end, elegant destination for weddings, anniversaries and romantic weekend getaways. They’re going for a total rebrand. Any focus on the building’s past function will glorify the Kirkbride plan and brand it as a place for healing (just like our spa!!!). And I’m sure they’ll do their level best to downplay the fact that there is a state psychiatric hospital right in the shadow of the building, where people with mental illnesses still live.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Which means we need to fight harder for the voices of those who have been and are being silenced, removed, and “painted over” even harder. Please join us at our next MITA meeting to discuss what we can do!

LikeLike

I wish I had written this. This project has horrified me from day 1!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, thank you, thank you! I am a Licensed Mental Health Counselor and this project hits home personally and professionally. My grandmother was institutionalized years ago, and I have worked professionally with people with bipolar issues, severe depression and schizophrenia. In addition, I have had my own mental health journey.

I am deeply troubled by this complex being turned into a “boutique” hotel, “cool” restaurant and a “hip” place to have a wedding. People suffered in these walls! I am all for restoration however, I would love to see the complex turned into a historical, educational and art center with lecture series, etc.

If you do not mind, I would like to share this blog piece on my personal and professional FB pages. I thought I was one of the only ones not pleased with the Hotel Henry. I will wait for your permission to share. Such a well written piece!

Sincerely,

Michelle

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing some of your experiences and for commenting in support of the points raised by the article. You (and any other person who reads this) absolutely have permission to share this article on your pages. Thank you, again!

LikeLike

Wonderful! The more folks that see this, the better. I saw after making the comment that you have a Facebook share button.

I appreciate your blog post so very much. I cannot get behind the “rah-rah” bandwagon on this project either. I agree that there is great social responsibility and advocacy needed.

Thank you, Michelle

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the interest of balance, I wanted to take a moment to respond. I am a former mental health therapist with twenty years of clinical experience, a descendant of several individuals treated at the Buffalo State Hospital (Asylum is an antiquated/politically incorrect term), and I am a volunteer for the Richardson Center Corporation and an historical researcher. I believe that its important to point out that none of the photographs shown here depicting treatment of persons with mental illness were taken within the Buffalo State Hospital. The Superintendent’s Reports describing treatment within the facility are available in the Library downtown and provide excellent insight into the care of patients within the facility.

While no state-run facility is perfect, they are not all on par with Bridgewater or Willowbrook either. While I cannot speak in an official capacity for the RCC, I can tell you that the organization (which is run separate fro Hotel Henry) has worked very hard to ensure that the history and dignity of those who resided within the walls of the institution is preserved. The RCC recently added a Patient Life Tour which is conducted within the untouched spaces of the Campus and I’d welcome anyone interested to join us to learn more about the history of this grand institution. As a descendant of former patients, I can attest neither the RCC nor the Hotel Henry is in any way disrespectful to the memory of those who received treatment within the confines of the Buffalo State Hospital. We honor the memories the patients, of H.H. Richardson, of Dr. Andrews, and even the life of the 19 year old fresco artist (Eugene F Melancon) who signed his name on the wall of the attic in 1879. For many of us, our connections to these buildings are personal and I’d never refer to my Great Aunt as a “Madwoman in the Attic”.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment, Mark. While I have no doubt that we have drastically different perspectives regarding mental health, I support conversation and diplomacy, and appreciate your attempt to communicate in defense of yourself, your line of work, and the institutions discussed in this article. I have made a note at the end of my article addressing the photos in the collage, to clarify my reason for including them even though they are not photos taken within the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane (which was its official name for most of its active existence, not something I made up in the interest of rhetorical effect). The issues raised in the article still stand in the face of some of your attempts at dismissal and patriarchal assurance. Whatever the institution is doing to honor the patient-victims is good but it’s not enough and more needs to take place to give voice to the people who were most affected by the former-asylum. I am afraid you are unfamiliar with feminist theory and literary criticism. Please do visit other pages on the site for more information on why this organization uses the term “madwoman.” It is a literary reference to a character named Bertha Mason from the novel “Jane Eyre.” I would be more interested in your aunt’s opinion than in your opinion, regarding the name to which she would prefer to be referred. Your aunt may have a very different opinion than you on what she should be called. It is a very common tradition for men to speak on behalf of women, and this patriarchal tradition which you have just enacted in your comment is one that has been repeatedly enacted formally within the doctor-patient relationship. Thank you for demonstrating it for those who read this article in the interest of studying language and systems of oppression. Madwomen in the attic is a way of taking back power for women who have been labeled against their will throughout history. The translation of the word “madwoman,” according to our organization, is “a woman mad at the system.” I wish your great aunt were here and could speak on her own behalf. All best to you and your education. JLM

LikeLike

Thank you for sparking this important discussion. We at the Richardson Center Corporation (the non profit owner of the site) continue to work to create a culture of respect for the history of the site, including former and current recipients of mental health care. We have worked closely with our neighbors at the Buffalo Psychiatric Center, and staff have served on our board and as docents for our historic tour program. The longer term interpretation and programming will be part of the Lipsey Buffalo Architecture Center at the Richardson and your comments serve as welcome input for its development! Thank you again for writing this piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, Ms. Krolewicz, for taking the issues my article has raised into consideration, and for reaching out to comment. I see that you have written me privately, as well. I look forward to continuing this conversation. All best, and, again, thank you for your comment and concern.

LikeLike

I wonder if any mental health consumers are on your board or serving as docents?

LikeLike

Although I know very little about the history of the Richardson Complex when it was an asylum, I was intrigued, reading Lauren Belfer’s CITY OF LIGHT to learn of the deep history of its intent–as a place dedicated to housing its residents/inmates (I’m sorry if my use of terminology is incompetent or insensitive) in a place that would be relatively humane and park-like. When I had the pleasure of eating a meal there, recently, and talking with one of the planners/managers of the current site, he very kindly gave some history and background, including the fact that much of the current Buffalo State campus was farm/garden for residents. Not to say this was a perfect or even utterly humane set of circumstances for residents–I would not know. But my father did work in the St. Louis state hospital for mental patients, and. . . at least on the face of things, it seems to me that the care and consideration that I.A. Richards gave to the campus is far superior to what I observed in St. Louis, in the 1960s. I guess what I am saying is that my own experience of the Richardson campus is not one of a sense that it was an inhumane place. Indeed, rather quite a bit to the contrary.

Perhaps what the current site needs (and it’s early days for the Hotel Henry–plenty of time to evolve in rightfully sensitive directions) is some historical context, here and there, in the form of historically-minded installation.

As a Buffalo resident and Buffalo booster, who has been graciously allowed to walk her dog (and, yes, to pick up after her dog 🙂 ) for a decade and a half, I am SO happy to see the beautiful site attended to and evolved in what seems to me a quite wonderful way. NOT to say this article seeks to vilify the H.H. But I do think it’s a bit disingenuous to post photos of horrors that may. . .or may not. . . be indicative of the Richardson Center’s history.

My two cents. And as a P.S. I highly recommend the gracious and accommodating H.H. as a lovely place to meet up for many reasons–including the 5 or so breakfasts I’ve enjoyed so far!

LikeLike

Elizabeth, It seems you felt the need to defend the institutions mentioned, as though you feel that I was personally attacking them, which is not the case. My article was written to raise awareness about and sensitivity toward the community of people who are labeled as mentally ill. Mentioning the strengths of our city and the beautiful qualities of the buildings and people in it is a deflection away from the issues raised in the article. The article does not claim that there are not benefits to the work being done by the RO Campus nor does it try to claim that H.H. is not a lovely, gracious, and accommodating place for the sector of people socioeconomically privileged enough to meet, eat, and stay there. I will respond to a few of your points, but think your comment was made because you felt, in some way, sorry for the RO Campus. My intention in writing the article was for you to think and care about learning about the histories of those who were directly affected by the asylum, those who are no longer with us, those who never had and will never have a voice in their treatment or a voice in general. I wish when you read the article that you would have been more concerned with the treatment of the human beings instead of defending the (intentions of) institutions. I was in high school when “City of Light” was published, and I believe I have a copy of it that I began but never finished reading. I would need to know specifically what was written in the *novel* about the intent of the Richardson Complex in order to analyze and critique it, but I also know that there was a romanticization of Buffalo involved in that novel, one that spoke to many people but one that did not necessarily address comprehensively the history of the Richardson Complex. You see, there are different perspectives that come into play, and my article is an attempt to encourage Western New Yorkers to think about a perspective that has not been considered– the perspective of those who have been institutionalized for mental illness. I encourage members of my community to be more suspicious of the presiding narrative. The narrative told about the Richardson Complex, the one to which you refer, is being told by those who have a stake in having it be depicted as a positive place with a positive history, and that is extremely problematic. Of course a corporate entity wants its consumers to see it in a positive light. It is normal. What I am asking is for the RO Campus to go above and beyond the status quo– to be unlike other corporate entities, to care about social justice. I wrote this in the hopes that some good would come: that stories not told would be told and honored, and that people would begin to care and think more about those who were and are affected by the mental health industry. Intentions matter, but histories matter, too. The article is about wanting to know what has been and will be done to recognize and render visible what has been rendered invisible about the people who were institutionalized in the insane asylum– I use that phrase because that is what it was. There is a reason we don’t use that phrase anymore and there is a reason the facility closed. It is hard to face the fact that even a well-intentioned entity could participate in something that actually harmed human beings. Your rose-colored way of looking at the complex is very understandable. You had a lovely meal, you were told a lovely story about the history of the institution, what is not to love… The problem is that you were told a specific story that is pleasant but that does not include the perspective of those who felt oppressed by the institution. You yourself said “at least on the face of things”– and I think that you made a good point there. That is the problem: the face of things. The face of things is a hospital putting up a sign that says it is number one in safety, while continuing to privately engage in dehumanizing, unethical practices. That is one example of how the face of things isn’t necessarily the truth of things. I encourage you to ask questions. I have no doubt that the restoration project has been conducted by well-meaning people; that, however, is not what this article is about. This article is about those who do not have a voice. Your focus on the institution, instead of on those who were victims of it, is part of the problem. I do not think it is at all disingenuous to post photos of horrors that may or may not have happened within the walls of the Richardson Center. The ambiguity is important because it reflects the question. The Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane is not some how exempt from being looked at with disturbance, as have been other insane asylums. It is not special. It was an insane asylum. An incarceratorial facility. We don’t have photos of what the patients over two centuries were like. Why would we? Do people take photos of the things they don’t want other people to know about? Not usually. Do they take photos so that, on the face of things (to use your phrase), things look different or better than they are? These are sincere and rhetorical questions that I hope you will think about. The fact that the patients at the BS Asylum can never tell us what they experienced or endured is the problem. I am trying to start a conversation that will give them a voice. The photos I included attempt to give them that voice for a moment, and to make it clear that insane asylums were not hotels and were not luxury vacation homes. I am glad you find the Richardson Complex beautiful for your walks with your dog. But that beauty does not detract from or make up for the suffering that many endured within the asylum. Both the beauty and luxury today and the darkness of yesterday must co-exist. And, yes, that might mean your walk feels a little less beautiful, but that’s what empathy is all about. Thank you for your two cents, and for the pleasant and kind tone of your comment. All best to you.

LikeLike

I believe the history of the Richardson Complex should be told, and honored. The hard history. Some of the horror of living there was the forced “treatment” and the incarceration – loss of freedom in every aspect of life. But even if you want to argue that the institution had good intentions, the fact is that people living there had symptoms of mental illness that likely were not well managed. I have a mental illness and I personally get a lot of relief from modern medications that were not available for most of the history of the Buffalo State Insane Asylum. I know many people do. In the past doctors didn’t know the source of mental illness let alone how to treat it. So I just want to say that living in the throes of acute psychosis is hell. And living in the throes of acute psychosis while surrounded by others in the same predicament is even worse. I was locked up on the ECMC psych ward for only 2 months in 2009. It was the hardest 2 months of my life. Partly because I was frustrated with the staff, but mostly because they were introducing me to a new antipsychotic very slowly (because I had had trouble tolerating it in the past) so I was psychotic for at least 7 weeks. My symptoms tormented me. I was terribly afraid of imaginary things. Terribly anxious and unable to be around others at times. And I had a hard time dealing with the symptoms of my roommate as I was struggling to manage my own. I was also really afraid of one guy on the ward, so I didn’t feel safe sleeping there knowing he was down the hall and we had no locks on our doors. What I’m trying to say is that the history of the Richardson Complex is horrifying regardless of the Asylum’s intentions. Untreated Mental Illness is horrifying and I think we could all agree that that story shouldn’t be swept under the rug, romanticized or forgotten.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In 1970 I worked in the Richardson Building as a COTA student. 1980 I was hired by Buffalo State Hospital. The “Towers” were still open. It is a bit disturbing now- touring through halls and rooms which were dorms full of sick people crying, laughing-all kinds of emotional sounds- and now it’s a Boutique Hotel. Don’t get me wrong. I am happy this magnificent building has been saved~but it’s original purpose was to provide daily care for the mentally ill as they struggled with reality. I didn’t see anything which acknowledged the care and treatment for those suffering Mental Illness. So much was accomplished. Many dedicated their lives to helping those with mental illness-the forgotten of our society.

LikeLike

Elizabeth, thank you for responding. Your response was sensitive and what you said is true and matters, and I admire the courage with which you spoke about your own experiences. Nearly six thousand people have at least glanced at this article and paused for a moment to think about the issue I attempted to raise. I hope we will be able to make a difference. You are not alone in your experience, and I am sorry that you have struggled. You are always welcome to join our organization and to attend our meetings– where you will be heard and where your perspective will be treated with dignity and respect. I will be attending one of the patient life tours soon, to provide input on the way in which the information is being presented. The overarching goal is for the voices of patients to matter and be heard rather than silenced. We can each work, individually, and all work collectively to move toward this goal. All best to you! Jess Lake Mason

LikeLiked by 1 person