History of the Consumer/Survivor Movement

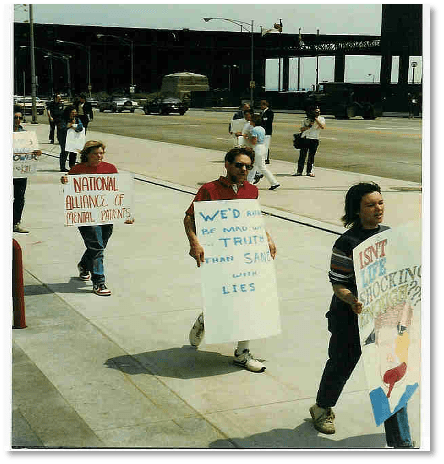

“We’d Rather be Mad with the Truth, than Sane with Lies”

Protest March 1970’s

History connects us with our past, with those who have gone before us and those who have earned remembrance. Persons currently working as peer supporters may not be aware of the rich history to which they now belong. The purpose of this account is to review the early history of the “Consumer/Survivor Movement” so that peers can learn about their roots, where they came from, as it applies to their work today. It is time to pay tribute and to honor those early pioneers who created the path so that we would someday benefit from their work and continue the journey.

The history of the consumer movement began in the 1970s, although there were many earlier pioneers. Among these, probably best known is Clifford Beers who wrote “A Mind that Found Itself” (1908), a book which ultimately led to the establishment of the American Mental Health Association. But the history that most directly relates to the activities of consumers/survivors today began at a time when the organized efforts of other civil rights groups were taking place, such as the Black/African American Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement for the right to vote, and less visible, the Physical Disabilities Movement and the Gay Movement, were in full force.

De-institutionalization of large state mental hospitals had begun in the late 1960s consequent with laws established to limit involuntary commitment. It was at this time that ex-patients began to find each other, form in small groups and organize in different cities all over the country, though initially they would not know about each other’s activities. They met in living rooms, church basements or community centers, expressing outrage and anger at a system that had caused them harm. Many had been forcibly subjected to shock treatments or insulin therapy. Seclusion Rooms and use of restraints (spread eagled, tied down) were a common practice, as it still is in some hospitals today. People knew about or were witness to many patients who had died and were still dying in institutions. Mental patients were used as un-paid labor at state hospitals and in some hospitals sheeting in cold packs were used as methods for behavioral control.

Homosexuals or others thought to be deviant were also being diagnosed and hospitalized as “mentally ill.” It was not until 1974 that the politically active gay community in the United States led the Board of Directors of the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The consumer/survivor movement began to include persons who had been harmed by the system for being gay. Mark Davis, a leader of this sub-movement, later used humor with his performance he called “Drag with a Tag.”

These ex-patients with whatever diagnosis given, felt de-humanized and degraded. Indeed, many of them had been told they had life-long mental illnesses and would never recover. Fully denying any belief in “mental illness”, their initial goals were to create a Liberation Movement–not to reform the mental health system— but to close it down. The term they most used to define them, was “ex-inmate.”

The politics of these groups were considered radical and their protests were often militant, but while this stronger more vocal arm of the movement was being organized, there were equally strong voices among the protesters who began to focus on self-help (defined as both personal and interpersonal help). They began to recognize people’s needs for support. The concepts of ex-patient- run alternatives that we are familiar with today, was conceived during this same period.

Among the first groups to form as an organization was the Insane Liberation Front, in Portland, OR (1970), followed by the Mental Patients Liberation Project in New York City and the Mental Patients Liberation Front in Boston (both in 1971), and in San Francisco, the Network Against Psychiatric Assault formed in 1972. (Chamberlin, 1990) The activities of these groups often included demonstrations at psychiatric hospitals and at conferences of the American Psychiatric Association; once forming a human chain that prevented conference attendees from entering. Another demonstration involved a month-long “sleep-in” at then Governor Jerry Brown’s office in California. Approximately 30 people occupied the office and remained there until their demands were heard. The primary issues were patients used as forced labor, un-investigated deaths, and abusive treatment. This demonstration brought attention to the issues and resulted in some changes particularly deaths of patients that were occurring in institutions. During this same period there were other protests held at psychiatric hospitals that used ECT. Marches took place in many cities hosting anti-psychiatry conferences, always featuring songs, chants and homemade signs with anti-psychiatry slogans.

Early protestors began to communicate with each other by means of a national newsletter and an annual conference. Madness Network News, (which featured the byline “all the fits that’s news to print”), was published in San Francisco for over ten years, with subscribers both nationally and internationally. The newsletter provided an outlet for people to find each other, share their stories, and political strategies for social change. Poetry and artwork was prominently included in every issue, much of it stark with depictions directly relevant to the political issues presented.

An annual Conference called, Human Rights against Psychiatric Oppression was held in different parts of the country most often on campgrounds or college campuses. The first of these conferences was in Detroit in 1972. People came by bus, by hitchhiking, and in cars packed full. Although most people were surviving on social security disability checks, and with no other income, they found a way to get to these conferences which were among the few opportunities that people had to network and share political views and strategies. One early and significant product emerging from one of these conferences was the development of a Bill of Rights, not too dissimilar from Patients Rights today. Meetings often lasted into the late hours while people debated issues and values and strategies. They tackled difficult subjects such as whether to take money from the government, whether to allow membership to persons who had not been hospitalized and whether to open their meetings to “sympathetic” professionals.

Judi Chamberlin, one of the early organizers, explains it this way, comparing our movement with other civil rights movements: “Among the major organizing principles of these movements were self-definition and self-determination. Black people felt that white people could not understand their experiences; women felt similarly about men; homosexuals similarly about heterosexuals. As these groups evolved, they moved from defining themselves to setting their own priorities. To mental patients who began to organize, these principles seemed equally valid. Their own perceptions about “mental illness” were diametrically opposed to those of the general public, and even more so to those of mental health professionals. It seemed sensible, therefore, to not let non-patients into ex-patient organizations or to permit them to dictate an organization’s goals.” (Chamberlin, 1990).

Though the movement believed in egalitarianism leaders did emerge. Names still familiar, such as Judi Chamberlin, though deceased in 2010, will always be remembered as the Mother of our Movement. Sally Zinman continues to be well known for her activism in California today. Howie the Harp, (now deceased) started organizing in New York City but later moved to the West Coast. Su and Dennis Budd are still active in Kansas. George Ebert continues to be active with Mental Patients Alliance in Syracuse, New York.

As the movement grew and changed, many leaders would eventually decide to sit at policy-making tables in order to have a voice, and to get funding for consumer-operated drop-in centers and other types of consumer-run programs. Some of the activists maintained their position of separatism and never participated in the evolving changes. Leonard Frank, one of the founders of the Network Against Psychiatric Assault in San Francisco, is an example. He chose instead to write a book, The History of Shock Treatment and has continued writing on different subjects, although always available for consultation.

In 1978 a landmark book was published: On Our Own: Patient Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System. This book, written by Judi Chamberlin, has been widely read, reprinted several times and is still considered an authority on the development of ex-patient controlled alternatives. One of the key principles she recommended is that alternatives be autonomous and in control of the hands of the users.

The 1980s was a transition time. The Federal Government began to take notice that ex-patients were organized and that they were operating successful programs independently without funds or outside support. The Community Support Program at the National Institute of Mental Health began to provide funding for these alternative programs.

In 1983 On Our Own of Maryland was the first to be funded with state funding: In 1985, the Berkeley Drop-In Center; the Ruby Rogers Drop-In Center, 1985, in Cambridge, MA; and in 1986, the Oakland Independence Support Center in Oakland California. The Berkeley Drop-in Center is still in operation and On Our Own of Maryland has transformed into a large statewide organization with many different programs.

In 1986, Sally Zinman, Howie the Harp, and Su and Dennis Budd, wrote the first manual with funds from the Federal Government; SAMHSA (Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration). Reaching Across provided information about self-help and how to operate a self-help support group. In a chapter on Support Groups, Howie the Harp describes how peers and professionals provide support differently. “Support is not therapy”, he wrote. “In support, the goal is to comfort, to be available as a caring friend, to listen, and to share the knowledge of common experiences….[while] In a therapeutic relationship the client is requested to change the way he/she thinks or acts.”

The first Alternatives Conference was held in 1985, in Baltimore with funding from the Community Support Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, again, with funding from NIMH. By this time there were a variety of different voices with different perspectives on mental illness, some with more moderate views that, while opposed to forced treatment, were not entirely against the medical model.

The conference with over 300 persons attending was challenged by a need to come up with a name to call them. The term “consumer” was eventually selected and it was meant to signify “patient choice” of services and treatment. Many people still add the word “survivor” which usually means having survived the mental health system more than having survived an illness. Issues around self-referential terms continue to baffle; no one really likes “consumer”, but another commonly acceptable term has not yet been found to replace it.

1985 was also the year when the final edition of the Madness Network News was published and thus marked the decline of radical militant groups. The conference on Human Rights and Against Oppression was also discontinued that year, and a more moderate tone began to reflect the movement.

In 1986, following numerous reports and investigations of abuse and neglect in state psychiatric hospital and findings of inadequate safeguards of patient rights, Congress passed the Protection and Advocacy Act for individuals with Mental Illnesses (PAIMI) Act. This act provided funding to existing disability advocacy groups in each state to investigate complaints of abuse, neglect or the denial of legal rights to all people in mental health facilities and to some living in the community. Many of the activist consumers sat on advisory committees to the state PAIMI program and continue to do so.

In 1988 funds were provided by SAMHSA for 13 self-help demonstration programs. Though these may have been successful most of these programs did not survive when the federal funding ran out.

More clients or consumers began to sit on decision making bodies. Language had changed from negative to positive. The activities of the militant groups changed to activists voicing strong opinions for change rather than organizing demonstrations to protest.

By the 1990s, many new consumer groups formed. Two national technical assistance centers were formed, The Self-Help Clearinghouse in Pa. under the direction of Joe Rogers, and the National Empowerment Center under the direction of Dr. Dan Fisher. Offices of Consumer Affairs were established at the state level in Departments of Mental Health and there was big growth in consumer- run alternative programs. Bill Anthony, Director of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, in Boston, in 1991, described it as the “decade of recovery.”

In 2000s we see an increase in gains for peer involvement in all areas of the mental health system. The most dramatic change is the development of roles for peer specialists in community settings and in inpatient settings. Peers are being trained to become peer specialists with a special peer-developed curriculum covering subjects such as “how to tell their story,” “WRAP” training, combating negative self-talk, stigma and discrimination and how to work with difficult clients, among others. Many specialized positions are being created for peers to work in emergency departments, in homeless programs, forensic facilities, and crisis alternatives. An increasing number of peer run alternatives are beginning to be developed including wellness programs and specialized drop-in centers and with job training programs and a variety of services. Peer Specialists are being trained in all parts of the country and following certification are working in community as well as inpatient settings. Crisis alternatives are being established with one of the first ones, the “Living Room”, created in Phoenix, Arizona. Training is being provided by internet and in extensive hands-on training programs. The Alternatives Conference is in its 25th year and has changed from an advocacy/activist focus towards goals of skills building and promoting wellness and peer support.

Unmarked cemetery and gravesites are being restored in many states with a national memorial planned at Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. with Larry Fricks and Pat Deegan leading the effort. The memorial will honor psychiatric patients whose graves were abandoned and forgotten.

A national organization was formed, The National Mental Health Coalition that is bringing statewide organizations and individuals together for advocacy and federal policy development with Lauren Spiro serving as national director. Five consumer and family led technical assistance centers have been federally funded to provide assistance to consumers throughout the country.

The list of our successes is endless. What we can expect in the future is up to the visionaries of today; fulfilling and implementing new strategies for involving persons with psychiatric histories in every level of decision making and employment at all levels in mental health agencies and facilities. We envision a time when persons with psychiatric disabilities are welcomed into society, integrated into jobs and living on their own or in assisted housing in communities. With all of us working together institutions may yet become obsolete. There is still work to be done. As our movement continues to unfold our membership might well include all of us working together in partnership, persons receiving services, family members, providers, consumer/survivors and friends!

References:

Beers.C. (1953). A mind that found itself. Garden City, New York; Doubleday.

Chamberlin, J. (1979). On our own: Patient –controlled alternatives to the mental health system. New York; McGraw-Hill

Chamberlin, J. (1990) The Ex-Patients Movement: Where We’ve Been and Where We’re Going.

Website: http://power2u.org/articles/hisotry-project/ex-patients.html

The Gardens at Saint Elizabeths: A National Memorial of Recovered Dignity: www.memorialofrecovereddignity.org

Zinman, Bluebird, Budd: History of the Mental Health Consumer Movement. (2009). (A webcast) go to: http://promoteacceptance.samhsa.gov/teleconferences/archive/training/teleconference12172009.aspx

For other information on History of the Consumer Movement go to:

People are already celebrating July 4th. Firecrackers are going off even days before the holiday. With Mae- Mae, my little dog, right up to my cheek, I held her, trying to hide her from the loud noises. I guess we can expect more of the same tonight.

I like the fourth of July because it is a symbol of freedom. A day I write in my journal or write poetry. I consciously allow parts of me to relax and loosen up. Quiet my mind, quiet my body. Stopping myself from constant motion.

Tell my left hand to be still on this day as usually I have fingers moving, wrists, folding into fists, or rubbing my legs with one of my not-in-use hands or wagging my foot. I try to hide this from other people though my granddaughter noticed it one time when we were driving in the car. “Would you stop doing that with your hand?” She asked, “You make me nervous.”

I am completely safe in my rocking chair, however. I can rock all I want not self-conscious If anyone notices or not.

I write this with the intention of it not being too long. It is hard for me to write as I am older, but I hope it will be sufficient for you to imagine what is missing from these abbreviated descriptions.

To start with I had a very unhappy life as a child. I was a sweet child at times but at other times disobedient. I would not listen to anyone. I could not control my bladder which was one of the things that made my teacher in kindergarten angry, and abusive to me. I don’t remember though I heard she had hit me. She was later fired! My mother attributed this problem to Grammy who had raised me when I was a toddler. “She had you on the pot all the time when you could barely walk. It was awful.”

My second-grade teacher found a way to deal with me—she put me in the corner, desk, and all, permanently. Her name was Miss Price. She had wiry hair that looked like she had a hairnet over it and was probably too old to teach. It was in this grade, I think, that they tested kids for their IQ. I fell into the bottom rung and was placed with the separated F class. But thankfully I don’t remember most of that.

I was still wetting my pants in the third grade and could not keep up with other kids, especially during recess when they played repetitive games or jumped rope. Anything I had to remember, I couldn’t.

That was and still is one of my main problems today. Ask me to tell you what I read in a book I just read, and I couldn’t tell you anything about it, and except for Julie Andrews and I don’t know most of the movie stars or what movies in which they were in. This information vacancy is one of the things I most try to hide.

The book The Reader is a book I do remember reading which had me in tears. I loved the affair between a young man and an older woman who had manipulated him with sex in exchange for him to read to her. His motivation was different, but they did fall in love. Love between two people was enough for me. I went searching and made a lot of mistakes, usually because I thought someone was attracted to me when, in fact, they weren’t. Especially when I was sure someone was a lesbian when they weren’t and who quickly stepped away from our budding friendship.

Friends were not usually the ones that lived near me. When you fail in your interactions with normal kids, you find kids across the tracks or who live in alleyways. There were three boys that lived in a shack who experimented sexually with me in a little tool shed. Their sister was to keep watch in case someone was coming. It was the first time I had been blackmailed. They told me they would tell my mother if I stopped.

On Halloween one night they climbed the fire escape that led off my room. “Trick or Treat,” they said to my mother who had a sack of candy they dug into, me standing next to her panting rapidly. My mother was dull anyway and did not suspect anything. She never knew what I was doing during the day or who I was with.

Shirley lived across the tracks with her drunk mother, but she was a great companion for a while. She taught me how to masturbate, and even on a bicycle with both of us riding. You must use your imagination. Shirley gave me lice which was not diagnosed until my itching resulted in my grandmother looking at my scalp. I remember the kerosene they put on my head on the rooftop outside our apartment.

I was a skinny child with multiple ailments, not eating, not sleeping, thinking bugs were crawling over me at night. “There are no bugs,” my mother said. I was terrified of my father, begging my mother to leave him.

I was so skinny, my father called my legs,” Two Toothpicks in an Olive”. I include this because when I told my grandchildren this, they laughed uncontrollably while we were taking a walk. I also include this because it was the closest, he got to saying something I thought was funny about me. Most of the time he called me a spoiled brat which I was.

I was a depressed child, that as I grew became more obvious. One of my mother’s best friends, who I happened to like to, because she was so literal and loud, said to my mother, “How’s Gayle,” the emphasis on How’s which you took to mean she was concerned about me, and maybe pitied me. By high school I lost my singing voice and could not sing Over the Rainbow with my soprano voice for a special school event. I started to lose my voice, even for talking. I was writing letters to God that asked me to save me or please let me die.

I thought I had it hidden well, my black shiny covered notebook with the small lines for writing, I can still almost see, but my mother found it in the attic. She was always cleaning even ordinary non-essentials. “You threw it out? I asked, incredulously, when a few years later I wanted to look to see what I had written. “Yes, I threw it out,” she said, emphatically, “It was too painful,” she said.

I think that was all she said. Case closed.

I do not want to omit my strengths. I was a great fantasizer of what could be and a great organizer when I determined something no one else was doing my age. I sold Christmas Cards from the Cheerful Card company that for several years they sent me a big box that barely fit in my small bedroom. I went all over town with a grocery cart selling them to people I didn’t know but could see how other people lived. I started a Junior Choir which I had no experience doing but I loved leading a group of kids. I remember the song; I would be true…but I forget the next line. I guess there were other things, like being a mother’s helper at the seashore one summer.

“But they are Jewish,” my grandmother said. “No, they aren’t,” I exclaimed. “I met them. They were very nice. I later learned that the word Kevitch was a Jewish name.

When I walked across the stage when I graduated, I wore thick white shoes that only old women wear because I thought something was wrong with my legs. I remember nothing else, except I had a nerdy boyfriend named Dennis, who much later, I realized he would have been a good catch, but at the time I wanted to be popular dating one of the popular boys that were way beyond my reach or reality.

My grandmother was determined I go to a “good” nursing school, always determined I would be a good nurse. I was surprised I was accepted because I remember my testing showing that I had poor reading retention.

At Jefferson, I had good, wonderful humorous friends who liked to tease me but also, we all laughed at the doctors and some of the things we experienced. I was in my third year when I did not believe I could be a nurse though I was not being kicked out like a lot of other girls. I was determined I was an orphan and one day, I walked up to the door of the Methodist Children’s Home and knocked.

I met the director, a beautiful looking man who said I should finish nursing school and met with me weekly to ensure I would stay in school. I have no idea whether the relationship was inappropriate or not, but he placed me on his lap every time I went and talked to me as a daddy might or maybe a therapist or maybe he even loved me. He recognized my inexperience with sex and played sexy word games with me.” F …k”, he would ask me to repeat. Other words you can imagine. I was always eager to go back as I was fascinated.

Sometime In the spring I had a patient who told me he had had elocution lessons. “Handsome, smooth, nice to hear him talk, he must have read my sexual neediness and readiness. Upon discharge I went to his apartment where he had me listen to Billie Holliday while we had sex. Being as I was small and so fragile, I was sure that I could never have a baby, at least that is what I think I thought, other than that I was just plain stupid. I got pregnant.

I had a secret I liked as well as imagining something growing inside of me. I kept except for a few of my nursing school friends who would later leave me as I was just too much. I wrote a letter to Dr. ML King though I was not a follower asking him if he knew a minister who would take me in as I had planned to start a day care center to keep my baby with me.

I got an immediate response. The only white member of his church would contact me. In a few days I had a letter from Esther Turner, a Quaker, and a member of Dr. King’s church.

My family blew up into scattered pieces like shattered glass as if this shock would cost them their reputations. My religious grandmother found an abortionist which I agreed to, also because I wasn’t sure I was stable enough to take care of a baby. But I was determined to go ahead with my original plans.

I graduated from nursing school one day, had an abortion the next and three days later was on a plane to Atlanta. I started an integrated school with a passion that was probably due in part to guilt. I also became friends with the King family and took the children to cultural events.

Marriage, three children later, I collapsed. I could barely function though I was still working. Seeing all kinds of psychiatrists and therapists and medications and high doses of vitamins, and finally primal therapy, I was acting like a baby and wanted to be a baby to be taken care of.

One of the incentives I had thinking Jacqi Schiff was my miracle new mother because I had read that she breast fed her children. I was obsessed with breasts, mostly because I didn’t have any. But I was sure I had not been fed right as a baby. I was sadly disappointed because that was not accurate. She was rarely home, and I knew that she sometimes breast fed one of her favorite children when she was presenting to an audience.

I would find my place of belonging with the radical anti-psychiatry group and would progress years later to create a career for myself. A career I would not have dreamed of. I was afraid of a lot of things, mostly rejection but not afraid of doing things differently and challenging the system was not difficult. But I always had a mentor who cared about me and believed in what I could do. Each one took me to the next step. I was being fed confidence I did not have but I did not want to let someone down who believed in me. Many years later I was given many awards and plaques, most of them thrown out as I had moved several different times. I threw out as I moved several times.

Don’t be deceived. As I moved along, I didn’t believe any of it inside. I was a walking impersonator of myself, going over and over what I had just done, a talk on a stage perhaps, going to my room crying or asking someone I trusted, “Was I okey? Are You sure?” Sometimes I stumbled but I do congratulate myself for meeting challenges I didn’t really feel capable of.

Today I am probably the happiest I have ever been. I still have not stopped though. Someone asked me to present at a conference in TN. I immediately was excited and somehow, I will have something to say. I still consult and there is a website started that contains my materials and others focused on the arts. What I don’t think people know is that I can’t stop saying, “Ok, here”” Ok, here”, “Ok here”, even in a whisper. It means I am here and am ok, at least that’s what I think it means, maybe it also means– I can go to the next thing– or maybe, it’s just part of being old. — ? My favorite part of the day is when I write a poem that seems to come out of nowhere, but I love just letting my words flow, occasionally hardly needing editing. Yesterday’s poem was Rotisserie Chicken. Today’s poem was Freedom.

Thank you for asking me to do this, Jessica Mason and other writers in “Madness in the Attic”.

I must give credit to some of my mentors:

Kevin Huckshorn, I always said “Wherever she goes I go.” One of those places was at a federal agency, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) where I was one of three peers on a team to reduce seclusion and restraint.

Marilyn Carmi who I could tell when I fell and wanted to die. “You always come through Darling”, she would say.

Natasha Reatig—the first Director of the Federal Protection and Advocacy. She was known more for her salons for underground artists and writers and film makers. We became instant friends when the Protection and Advocacy Protection under federal guidelines were formalized in Saint Lewis, Mo.

Rita Cronise, a director at the Academy for Peer Support Training in New York

Henrietta, that was Me, a character I developed who wore sexy attire and was confused. One Ringy Dingy, One Dingy Ringy……

Gayle Bluebird, AKA Bluebird, has been a pioneer working to change the culture of the mental health system for many years. She has helped to develop peer support programs and training curricula for peer specialists. She is known for promoting the arts for people to heal from trauma and emotional abuse and has formed a national network of artists, writers and performers who tell their mental health stories through art. She has received many awards, including the prestigious “Voice Award” from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA) in 2010. Occasionally she still presents at several consumer/survivor conferences and does some consulting. A version of retired, at eighty, she spends much of her time writing poetry while living in a senior apartment with her little dog, Mae-Mae in Jacksonville, FL. Her third book of poetry, Lantern to My Soul, and her latest book, Tootles ‘Tales,’ are available on Amazon.

You can find her on Facebook or email her at: gaylebluebird1943@gmail.com.